That Incredible Christian

by A. W. Tozer

The current

effort of so many religious leaders to harmonize Christianity with

science, philosophy and every natural and reasonable thing is, I

believe, the result of failure to understand Christianity and, judging

from what I have heard and read, failure to understand science and

philosophy as well.

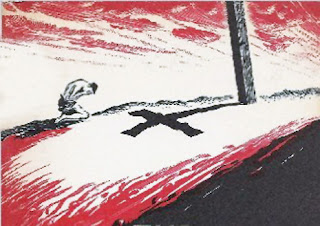

At

the heart of the Christian system lies the cross of Christ with its

divine paradox. The power of Christianity appears in its antipathy

toward, never in its agreement with, the ways of fallen men. The truth

of the cross is revealed in its contradictions. The witness of the

church is most effective when she declares rather than explains, for the

gospel is addressed not to reason but to faith. What can be proved

requires no faith to accept. Faith rests upon the character of God, not

upon the demonstrations of laboratory or logic.

The

cross stands in bold opposition to the natural man. Its philosophy runs

contrary to the processes of the unregenerate mind, so that Paul could

say bluntly that the preaching of the cross is to them that perish

foolishness. To try to find a common ground between the message of the

cross and man's fallen reason is to try the impossible, and if persisted

in must result in an impaired reason, a meaningless cross and a

powerless Christianity.

But

let us bring the whole matter down from the uplands of theory and

simply observe the true Christian as he puts into practice the teachings

of Christ and His apostles. Note the contradictions:

The

Christian believes that in Christ he has died, yet he is more alive

than before and he fully expects to live forever. He walks on earth

while seated in heaven and though born on earth he finds that after his

conversion he is not at home here. Like the nighthawk, which in the air

is the essence of grace and beauty but on the ground is awkward and

ugly, so the Christian appears at his best in the heavenly places but

does not fit well into the ways of the very society into which he was

born.

The

Christian soon learns that if he would be victorious as a son of heaven

among men on earth he must not follow the common pattern of mankind,

but rather the contrary. That he may be safe he puts himself in

jeopardy; he loses his life to save it and is in danger of losing it if

he attempts to preserve it. He goes down to get up. If he refuses to go

down he is already down, but when he starts down he is on his way up.

He

is strongest when he is weakest and weakest when he is strong. Though

poor he has the power to make others rich, but when he becomes rich his

ability to enrich others vanishes. He has most after he has given most

away and has least when he possesses most.

He

may be and often is highest when he feels lowest and most sinless when

he is most conscious of sin. He is wisest when he knows that he knows

not and knows least when he has acquired the greatest amount of

knowledge. He sometimes does most by doing nothing and goes furthest

when standing still. In heaviness he manages to rejoice and keeps his

heart glad even in sorrow.

The

paradoxical character of the Christian is revealed constantly. For

instance, he believes that he is saved now, nevertheless he expects to

be saved later and looks forward joyfully to future salvation. He fears

God but is not afraid of Him. In God's presence he feels overwhelmed and

undone, yet there is nowhere he would rather be than in that presence.

He knows that he has been cleansed from his sin, yet he is painfully

conscious that in his flesh dwells no good thing.

He

loves supremely One whom he has never seen, and though himself poor and

lowly he talks familiarly with One who is King of all kings and Lord of

all lords, and is aware of no incongruity in so doing. He feels that he

is in his own right altogether less than nothing, yet he believes

without question that he is the apple of God's eye and that for him the

Eternal Son became flesh and died on the cross of shame.

The

Christian is a citizen of heaven and to that sacred citizenship he

acknowledges first allegiance; yet he may love his earthly country with

that intensity of devotion that caused John Knox to pray "O God, give me

Scotland or I die."

He

cheerfully expects before long to enter that bright world above, but he

is in no hurry to leave this world and is quite willing to await the

summons of his Heavenly Father. And he is unable to understand why the

critical unbeliever should condemn him for this; it all seems so natural

and right in the circumstances that he sees nothing inconsistent about

it.

The

cross-carrying Christian, furthermore, is both a confirmed pessimist

and an optimist the like of which is to be found nowhere else on earth.

When

he looks at the cross he is a pessimist, for he knows that the same

judgment that fell on the Lord of glory condemns in that one act all

nature and all the world of men. He rejects every human hope out of

Christ because he knows that man's noblest effort is only dust building

on dust.

Yet

he is calmly, restfully optimistic. If the cross condemns the world the

resurrection of Christ guarantees the ultimate triumph of good

throughout the universe. Through Christ all will be well at last and the

Christian waits the consummation. Incredible Christian!